Flu vaccine: is it effective in preventing infection, hospitalization, and death?

Multiple studies conducted over the last 25 years suggest ZERO or NEGATIVE effectiveness of various flu vaccines

In the United States, every year, approximately half of the population is vaccinated against the flu – 45-50% of adults and 50-55% of children.

Have you ever wondered how effective the flu vaccine is against infection, hospitalization or death from complications caused by the flu?

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the latest vaccine from the 2024/2025 season reduced the risk of infection by 32-60%, and the risk of hospitalization by 41-78%. It is not 100%, far from ideal, but it’s better than nothing. Of course, if it is really so. But is it so?

In April, a preprint of a study from the Cleveland Clinic in the United States was released, in which all employees (53,402 employees, 82% of whom had been vaccinated against the flu) were followed from October 2024 to April 2025.

The researchers plotted the cumulative rate of flu cases for the vaccinated and unvaccinated and got an unexpected result. The vaccinated had a 27% higher rate of flu infections than the unvaccinated. A statistically significant difference. In other words, the vaccine increased the risk of getting the flu.

To be fair, there is criticism from biostatisticians that the two groups were not adequately adjusted for two variables related to the testing. We will see in the final peer-reviewed version of the paper how this issue is addressed, but even the most robust criticism calculated that at best, the flu vaccine for the 2024/25 season would be -1.6% effective.

The question is, who is closer to the truth - the CDC or the Cleveland Clinic researchers?

After all, if it doesn’t reduce the risk of flu infection, why would anyone get vaccinated with an ineffective vaccine?

Here’s why: it reduces the risk of hospitalization!

Definitely, no one wants to be hospitalized for possible complications from the flu, and this argument is rock-solid. If the flu vaccine offers even a 30% (statistically significant) protection against hospitalization, it’s still better than nothing. As shown above, the CDC calculated that for the 2024/2025 season, flu vaccine recipients had a 41-78% lower hospitalization rate than unvaccinated individuals. But given that the Cleveland Clinic researchers found negative or at best zero effectiveness against infection, the CDC’s estimates must be taken with a grain of salt.

Let’s look at what other studies have found about how much flu vaccines have protected against hospitalization over the years.

The CDC study for the 2021/2022 season

In 2022, the CDC published its own study on the effectiveness of the 2021/2022 flu vaccine against hospitalization. Using a test-negative design and adjusting for a number of confounding factors (calendar time, vaccination site, age, gender, race, and ethnicity), the results were unexpected and very disappointing. The most vulnerable category, adults over 65, had no protection at all against hospitalization due to flu complications. The vaccine also failed for those between 18 and 64 years of age (no statistically significant difference with the unvaccinated), except for the subgroup without immunocompromising conditions.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs study for the 2022/2023 season

The previous study was for the 2021/2022 season, at a time when the SARS-CoV-2 virus was dominant everywhere. Is there data for the next season when the flu was back in a big way? Fortunately, there is. The US Department of Veterans Affairs published a study in 2023 comparing the risks of death for hospitalized veterans from COVID and influenza for the 2022/2023 season. The table shows a lot of data. For example, one can see that the hospitalized were quite old (mean age >73 years). For our analysis, the most important fact is that data is provided on the percentage of hospitalized for influenza who received the flu vaccine and the percentage of hospitalized for COVID who received the flu vaccine.

Why is this data important? Because we need these numbers to calculate the effectiveness against hospitalization caused by influenza. In the calculation, the so-called test-negative design is used. According to this method, the following formula is used to calculate the odds ratio:

We take the corresponding numbers from the table in the paper, insert them into the test-negative design formula and obtain that the flu vaccine effectiveness for hospitalization is:

The parameter p is the probability that the difference between the hospitalization odds of vaccinated and unvaccinated people is the result of chance. Since p=70% which is much higher than the 5% threshold, the relative difference of 1.8% is indeed the result of chance, i.e., vaccinated and unvaccinated people had the same risk of being hospitalized due to flu. Again an unexpected and disappointing result.

So far we have only seen studies from the US and from the last few years. Perhaps a study conducted in another country from the pre-COVID period showed high effectiveness against hospitalization for flu. Let's have a look at a massive study from the United Kingdom.

The UK Study for the period 2000-2014

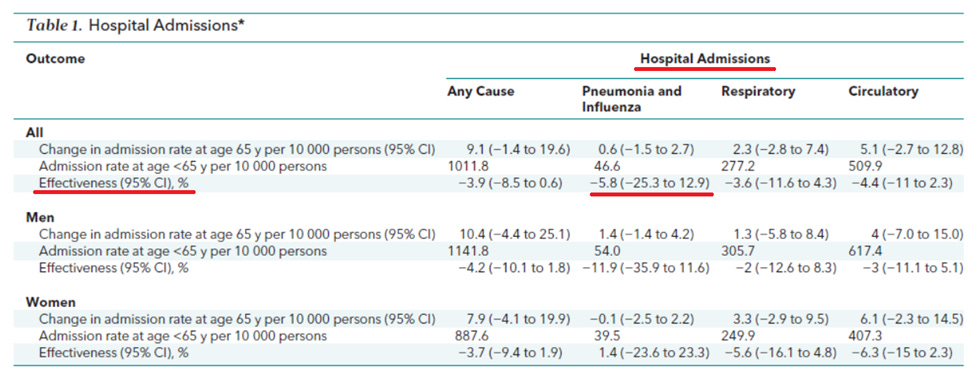

Researchers in this huge study evaluated outcomes for people aged 55 to 75 in England and Wales between 2000 and 2014. So again, elderly people. They found 170 million episodes of care and 7.6 million deaths, and that turning 65 was associated with a statistically and clinically significant increase in seasonal flu vaccination rates. However, they found no evidence that vaccination reduced hospitalizations in older people. The effectiveness was -5.8% (95% CI, -25.3% to 12.9%). According to the authors of the paper, the estimates were precise enough to rule out the results of many previous studies.

If the flu vaccine doesn’t prevent flu infection, it doesn’t prevent hospitalizations due to flu, then why would anyone get vaccinated with an ineffective vaccine?

Here’s why: it reduces the risk of death!

Absolutely! If the vaccine protects against death, especially in the elderly (who represent the highest risk category), then the vaccine is worth getting. No doubt about that.

The previously mentioned British study, in addition to computing effectiveness against hospitalization, also assessed the effectiveness of the flu vaccine against death. What did the researchers find? See the following table.

They estimated the effectiveness against death from pneumonia and influenza at -17.3% with a confidence interval -40.7% to 6%. This is a negative effectiveness, but there is no statistically significant difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated people in terms of pneumonia and flu mortality because the confidence interval covers the zero value. So, there is no evidence that the vaccine provided protection against death.

However, note this concerning result. The upper limit of the confidence interval is only 6%, i.e. much closer to zero than the lower limit of -40.7%. This means that there was a trend (almost statistically significant) towards negative effectiveness. In men, this trend was much more pronounced: -26.5% with a confidence interval of -56.1% to 3%!

So far, we have looked at studies showing negative or zero protection against infection for middle-aged people (the Cleveland Clinic study) and zero protection against hospitalization or death for elderly people. But what about children? Are flu vaccines beneficial for children? According to the above cited CDC study for the 2024/2025 season, children had a reduced risk of infection and hospitalization, but due to the contradictory results with the Cleveland Clinic study, it is controversial.

Double-blind, randomized clinical trial in Hong Kong

13 years ago, in 2012, researchers from the University of Hong Kong published a paper reporting the results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which they randomly assigned children aged 6 to 15 years to receive the 2008–2009 seasonal trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV; 0.5 mL Vaxigrip; Sanofi Pasteur) or placebo. The children were monitored for illness through symptom diaries and telephone calls, and home visits were made in cases of illness in any household member during which nasopharyngeal swab specimens were collected from all household members.

Among the 115 children who were followed, the median duration of follow-up was 272 days. They identified 134 episodes of acute respiratory infections, 49 of which were febrile.

Were vaccinated children protected from influenza infection?

“There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of confirmed seasonal influenza infection between recipients of TIV or placebo, although the point estimate was consistent with protection in TIV recipients (relative risk [RR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], .13–3.27).”

Put another way, the effectiveness against influenza infection was 34%, but without a statistically significant difference because the confidence interval covers zero and ranges from -227% to 87%. Therefore, there is no evidence that the vaccine provided protection against influenza.

It should however be noted that this study represents the gold standard in clinical trials because it was randomized, double-blind and the control group received placebo. Therefore, its results suggest causality and carry more weight than observational studies such as the test-negative design trials commonly used by the US CDC.

Does the flu vaccine increase the risk of other respiratory infections?

The results from the Hong Kong study show a striking 4.4-fold increase in the risk of other respiratory infections (rhinoviruses and coxsackie/echoviruses) with a 95 percent confidence interval of 1.31–14.8.

Why would the flu vaccine increase the risk of infections with other respiratory viruses? One explanation from the authors of the paper is that receiving the trivalent flu vaccine may increase immunity against influenza at the expense of reduced immunity to non-influenza respiratory viruses, through some unknown biological mechanism.

But this is not the only study to suggest that the flu vaccine increases the risk of infections with other respiratory viruses. In a 2014 Australian study, children vaccinated against influenza were 1.6 times (p = 0.001) more likely than unvaccinated children to get a non-influenza respiratory infection.

In the following years, the CDC funded a three-year study published in the Vaccine to analyze the risk of illness after influenza vaccination compared with the risk of illness in unvaccinated individuals. The study, which included healthy subjects, found a 65% increased risk (Relative Risk: 1.65, 95% CI [1.14, 2.38]) of acute non-influenza respiratory illness within 14 days of receiving the influenza vaccine. The most common viruses found were rhinovirus, enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and coronaviruses.

Excellent! Thanks!

I also remember the Cochrane about flu vaccine. It is nothing there too!

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6/full